Baawaating – Place of the Rapids

Pre-Contact Era (Before 1600s)

- 8,000+ years ago: Indigenous peoples inhabit the Great Lakes region.

- Anishinaabe (Ojibwe, Odawa, Potawatomi) peoples establish a cultural, economic, and spiritual presence at Baawitigong (“place of the rapids”).

- The St. Marys River rapids are vital for whitefish harvesting, trade, and spiritual ceremonies.

1600s: First Contact

- 1615–1622: French explorers and missionaries (e.g., Étienne Brûlé, Samuel de Champlain) travel through the region.

- 1668: Jesuit missionaries, including Father Jacques Marquette, establish a mission — the oldest European settlement in Ontario.

- Indigenous women and fur traders form alliances through intermarriage, creating Métis communities.

1700s: Fur Trade Flourishes

- The area becomes a strategic fur trade hub.

- Indigenous peoples are central to trapping, guiding, and managing trade routes.

- Cultural and political gatherings continue at the rapids.

1800s: Colonization and Treaties

- 1812: War of 1812 affects Indigenous trade and autonomy; alliances with British and Americans.

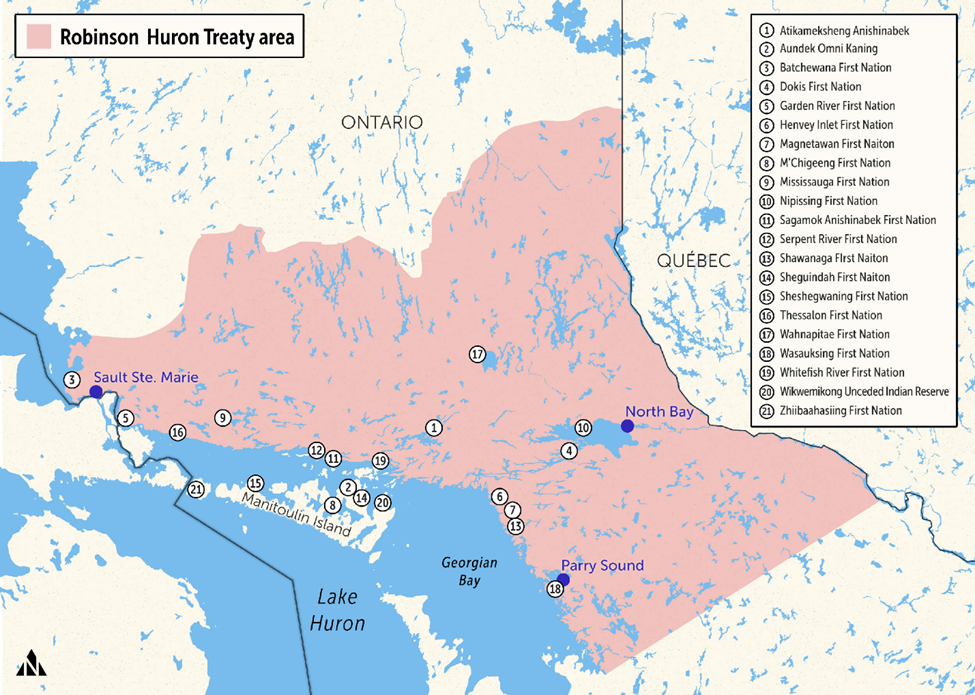

- 1850: Robinson-Huron Treaty signed with the British Crown.

- Anishinaabe cede land in exchange for annuities and the right to hunt, fish, and occupy reserves.

- 1850s–1900s: Government policies and settlement restrict Indigenous mobility and access to land.

Late 1800s–1900s: Residential Schools & Assimilation

- 1873: Shingwauk Indian Residential School opens. Intended by Rev. Edward Shingwauk (Anishinaabe) as a place of learning but becomes part of the broader residential school system.

- 1960s–70s: Residential school closes; survivors begin sharing their stories.

Late 1900s–Present: Revitalization and Resistance

- Indigenous-led movements emerge to reclaim language, culture, and governance.

- 2018: Ontario Superior Court rules that the Crown failed to uphold its duty under the Robinson-Huron Treaty regarding annuity increases.

- Present-day: Garden River First Nation, Batchewana First Nation, and Métis communities thrive. Shingwauk Residential Schools Centre supports education and reconciliation.

Late 1900s–Present: Revitalization and Resistance

- Indigenous-led movements emerge to reclaim language, culture, and governance.

- 2018: Ontario Superior Court rules that the Crown failed to uphold its duty under the Robinson-Huron Treaty regarding annuity increases.

- Present-day: Garden River First Nation, Batchewana First Nation, and Métis communities thrive. Shingwauk Residential Schools Centre supports education and reconciliation.

Robinson Huron Treaty 1850 | Ontario

“This agreement, made and entered into this ninth day of September, in the year of our Lord one thousand eight hundred and fifty, at Sault Ste. Marie, in the Province of Canada.

Between the Honorable William Benjamin Robinson, of the one part, on behalf Her Majesty the Queen, and Shinguacouse Nebenaigoching, Keokouse, Mishequonga, Tagawinini, Shabokishick, Dokis, Ponekeosh, Windawtegowinini, Sha Wenakeshick, Namassin, Naoquagabo, Wabakekik, Kitchepossigun by Papasainse, Wagemaki, Pamequonaisheung, Chiefs: and John Bell, Paqwatchinini, Mashekyash, Idowekesis, Waquacomick, Ocheek, Metigo-Minwatachewana, Minwawapenasse, Shenaoquom, Oninge-Gun, Panaissy, Papasainse, Ashew Asega, Kageshew Awe-Tung, Sha Wonebin; (also Chiefs Muckata, Mishoquet and Mekis), and Misho-Quetto and Asa Waswanay and Pawiss, principle men of the Ojibwa Indians, inhabiting and claiming the Eastern and Northern Shores of Lake Huron, from Penetangushine to Sault Ste. Marie, and thence to Batchewanaung Bay, on the Northern Shore of Lake Superior: together with the Islands in the said Lakes, opposite to the Shores thereof, and inland to the Height of land which separates the Territory covered by the charter of the honorable Hudson Bay Company from Canada; as well as all unconceded lands within the limits of Canada West to which they have any just claim, of the other part, witnesseth: …

Residential School History

From the late 1800s to 1996 more than 150,000 First Nation, Métis and Inuit children were taken from their families to attend residential schools. The goal was to remove the Indigenous lifestyles of the children and replace them with Christian beliefs. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission released a report stating that 1 in every 50 students died, with 4,100 having officially died. However, as of 2022 more than 7,000 unmarked graves have been identified at former residential schools in Canada.

Former Justice Murray Sinclair “Every Aboriginal person has been affected directly or indirectly by the residential schools.”

The cultural genocide that occurred in Residential school’s lead into the effects of poverty, homelessness, violence, the criminal justice system, racism and mental health and addictions issues for First Nations people. The effects of colonization have been pared to the effects of individuals with post-traumatic stress disorder. The traditional Indigenous government system ensured that the needs of people were met, including health, work, and food. Poverty was non-existent during these times, which changed drastically once Indigenous people fell under colonial government rule.

Shingwauk Kinoomaage Gamig

The Shingwauk school opened in 1873 in Garden River, ON, burning down within days of opening. It was replaced two years later with a school built near Sault Ste. Marie. In 1931 the school was condemned. A new school opened in 1935, at which time the school merged with the Wawanosh girls’ school. In the 1950s, Shingwauk students began attending local day schools. In 1969 the federal government took over the administration of the school, closing it the following year. The former school is home to Algoma University College and the Shingwauk Project Residential School Archive and Research Centre.

Shingwauk Hall, the school’s primary structure, was built in 1934-35 to replace the original school building which dated to the late-19th century. It is one of the few remaining residential school buildings in Canada. Other buildings and landscape elements related to the former school include the Shingwauk Memorial Cemetery (1876), Bishop Fauquier Memorial Chapel (1883), the former principal’s residence (1935), the former woodworking shop (1951), and Anna McCrea Public School (1956). The Shingwauk IRS site is one of the few surviving residential school sites with a notable ensemble of preserved built and landscape elements that continue to testify to the long history of the residential school system in Canada.

The Sixties Scoop

The Sixties Scoop refers to a period in Canadian history, roughly from the 1950s through the 1980s, during which thousands of Indigenous children were forcibly taken from their families by child welfare authorities and placed into non-Indigenous foster homes or adopted by families across Canada, the United States, and beyond. This widespread practice was carried out under the belief that Indigenous children would have better lives if assimilated into Euro-Canadian culture, often without the consent of their families or communities. As a result, many of these children grew up disconnected from their heritage, language, and identity, leading to long-term impacts on their mental health, sense of belonging, and cultural continuity. The Sixties Scoop is now recognized as a grave injustice and a key part of the broader legacy of colonial policies that have harmed Indigenous peoples in Canada.

Indian Day Schools in Canada

Day Schools for First Nations people were government- and church-run institutions in Canada that operated similarly to Residential Schools but allowed children to return home at the end of the day. Despite this difference, Day Schools also aimed to assimilate Indigenous children into Euro-Canadian culture by forbidding the use of Indigenous languages, suppressing cultural practices, and promoting Christian teachings. Many students experienced emotional, physical, and psychological abuse, and the schools played a significant role in the disruption of Indigenous identity, community bonds, and traditional knowledge. The harmful legacy of Day Schools continues to impact survivors and their families today.

Indian Act

The Indian Act, first passed in 1876, is a Canadian federal law that governs many aspects of the lives of First Nations people, including band governance, land use, status, and cultural practices. It was created as part of colonial efforts to control and assimilate Indigenous peoples and has been widely criticized for its oppressive and paternalistic policies. Over time, the Act has been amended, but many of its provisions continue to limit the autonomy of First Nations communities. Despite this, it remains a central piece of legislation affecting Indigenous rights and governance in Canada today.

National Inquiry for Murdered and Missing Indigenous Women and Girls

The RCMP estimates that 1,200 indigenous women and girls have gone missing between 1980-2012, however, the Native Women’s Association of Canada puts the number close to 4,000.

The Final Report of the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Woman and Girls was released in 2019.

This calls for legal and social change to resolve the crisis that has devastated indigenous communities across Canada.

NWAC - Native Women's Association of Canada

The Native Women’s Association of Canada released its own action plan in 2021. The plan consists of 65 actions that will address the Calls for Justice.

Joyce’s Principle: Joyce Echaquan

Joyce’s Principle aims to guarantee to all Indigenous people the right of equitable access, without any discrimination, to all social and health services, as well as the right to enjoy the best possible physical, mental, emotional and spiritual health.

Jordan's Principle

Jordan’s Principle is a child-first, needs-based principle that ensures First Nations children have equitable access to health, social, and educational services.It was named after Jordan River Anderson, a young boy from Norway House Cree Nation in Manitoba. Jordan was born with complex medical needs and spent over two years unnecessarily in the hospital because the federal and provincial governments could not agree on who should pay for his at-home care. Tragically, Jordan passed away in 2005 at the age of five, without ever being able to live in a family home.As a result, Jordan’s Principle was created to make sure no First Nations child experiences denials, delays, or disruptions in services because of jurisdictional disputes between governments.